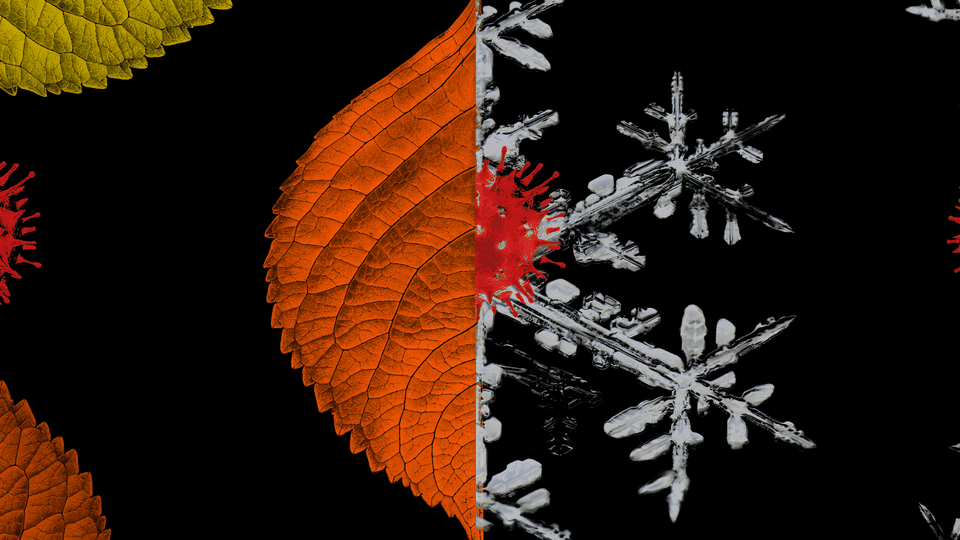

The COVID-19 Fall Surge Is Here. We Can Stop It.

What we can learn from other countries to avoid the worst-case scenario

COVID-19 cases are rising in parts of New York City, and the mayor is threatening business and school closures. Across other parts of the United States and Western Europe, outbreaks are spiraling out of control. President Donald Trump is comparing the coronavirus pandemic to the seasonal flu on Twitter.

What month is this again? Hundreds of thousands of deaths since the pandemic began in March, we seem to be right back where we started, like passengers trapped on a demonic carousel.

Everything could still get worse. This week, Anthony Fauci warned of a new surge in cases, as Americans move from the virus-dispersing outdoors into more crowded and less-ventilated public spaces in colder months.

Or everything could get better. Thanks largely to new treatments and more knowledge about this virus, hospitalization-fatality rates have declined across Europe and the United States. As a result, new surges are less likely to re-create the springtime spike in deaths. Individuals are also far more conscientious and alert to the risks.

To build on these new advantages, American and European citizens have to embrace both empiricism and imperfection. Thinking empirically means paying attention to the collective findings of scientific experts, rather than relying on partisan cues (But the president says …) or the behavior of our friends (But my friends don’t care about …). We also have to be prepared to accept less-than-perfect solutions, such as rapid tests and masks, to bring society to a sustainable equilibrium of normalcy, rather than toggle between draconian lockdowns and ruinous free-for-alls for another year. A silver bullet may be months away, or longer. But bronze bullets abound.

America’s fall surge seems chaotic and scattershot, like every chapter of this pandemic. In the U.S., it is concentrated in the Midwest and northern Plains, especially in the Dakotas, Montana, and Wisconsin.

COVID-19’s resurgence isn’t just happening in America. Infections are now rising in Spain, France, and the United Kingdom—all of which currently have more new daily cases per capita than the U.S. This summer, it seemed as if America’s COVID-19 response was uniquely horrific and embarrassing. Today, the group of embarrassed countries is more crowded.

In France, where cases have reached a record high since widespread testing began, bars in Paris have been ordered to close for several weeks. In the U.K., where new cases are up eightfold since August, The New York Times has reported that pubs are packed and that supermarket aisles are filled with mask-free shoppers. In Spain, Madrid residents have been asked to not leave the city, and leaders are blaming the party habits of young people.

Spain’s outbreak, the worst of the bunch, carries a valuable lesson for other countries and metros experiencing the fall surge. When the nation’s lockdown ended in June, cases started to increase almost immediately, like water spewing out of an unblocked hose. By September, Spain was declaring more new confirmed COVID-19 cases per capita than the U.S. did at the peak of its summer outbreak. In lieu of deciding on a durable strategy, Spain merely swapped one unsustainable plan, lockdown, for another, uncontrolled outbreaks.

The outlook isn’t so dire globally, however. Countries with fewer than 50 coronavirus deaths per 1 million residents include Indonesia (40), Australia (35), Japan (13), South Korea (8), and Vietnam and Taiwan (both under 0.5). This “under-50” group notably includes almost no large countries in Europe or the Americas, whose most populous nations have suffered far more fatalities as a share of residents. In the U.S., the U.K., Spain, Italy, Mexico, and Brazil, deaths per million sit roughly between 600 and 700.

What’s so special about the most successful COVID-19 responses? The honest answer is that we can’t be sure yet. In the coming years, we may learn that the good outcomes across Africa and East Asia were mostly the result of Vitamin D levels, or age distributions, or immunity conferred from exposure to other coronaviruses. More likely, however, is that they got the response right because they understood a certain story about how this virus operates:

COVID-19 is airborne, overdispersed, and often asymptomatic. That means it spreads mostly through tiny spray droplets commonly produced by people talking loudly in crowded, unventilated spaces over long periods, leading to “super-spreading” clusters—where one sick person infects many healthy people—that account for a large share of total infections. Infected people without symptoms might also be super-spreaders.

This is a relatively simple story, and in all likelihood, it’s incomplete. But it contains several lessons that can help countries and communities avoid an even worse fall surge, right now.

From South Korea: Fewer lockdowns—but more masks and tracing

Many Western countries have responded to COVID-19 outbreaks by immediately shutting down as much of society as is feasible. This approach is economically catastrophic in the short term, unsustainable in the long term, and possibly unnecessary in any term—if the authorities respond swiftly with other measures. South Korea had an extremely successful COVID-19 response, and it never adopted widespread lockdowns. Rather, it used a combination of universal mask wearing, limits on crowds, contact tracing to quickly identify potentially infected individuals, and quarantine or isolation guidance to keep the sick and potentially sick away from healthy people.

“We were never on lockdown,” Paul Choi, a consultant who lives in Seoul, told me. Instead, South Korea focused its closures on places like bars and nightclubs, where crowding was inevitable, and encouraged universal mask wearing. “Almost everybody is wearing masks,” Choi said. “If you don’t wear masks, you get looks on the street.”

The objection to masks in the U.S. (besides itchiness and tyranny) is that they’re crude, misused, and unproven in randomized-control trials. This much is true: Masks aren’t perfect. But their imperfection is often enough to make this disease less likely to spread—and less severe for those who get it. A new research preprint estimates that when an infected person and a non-infected person both wear masks, that can reduce the chance of transmission by up to 80 percent compared with a scenario where neither is masked. Joshua T. Schiffer, an infectious-disease researcher at the University of Washington who co-wrote the study, found that if the healthy masked individual is infected, her viral dosage is slashed by a factor of 10. This reduces the likelihood that she develops a severe case of COVID-19. A larger body of research finds that masks reduce the spread of aerosolized diseases like COVID-19.

From Vietnam: The benefits of clear and accurate public-health communication

The Trump administration’s consistent lying on issues including, but by no means limited to, the pandemic has created a vacuum of institutional trust at the very moment it is most necessary.

Vietnam offers a particularly vivid example of what candid public-health communication might look like. Its Ministry of Health first alerted citizens to the threat of an outbreak during the second week of January. In February, its National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health released a song—“Ghen Co Vy,” meaning “Jealous Coronavirus”—that advocated for social distancing and hand-washing. In April, the country imposed a fine on people who posted “false, untruthful, or distorted” information on social media. “This messaging engendered a community spirit in which every citizen felt inspired to do their part, whether that was wearing a mask in public or enduring weeks of quarantine,” a team of health and economic researchers from Vietnam and Oxford wrote in an essay summarizing the country’s response to the virus. To date, the nation of 95 million has an official COVID-19 death count of 35, which is roughly the number of Americans who die of this disease every hour and a half.

From Japan: Open schools, but do it safely

Many cities have refused to open public schools, for fear that doing so will trigger a mass outbreak, and still others—including Boston—are delaying in-person instruction as positivity rates rise. As a result, America’s pandemic is becoming an education and family crisis, one that is particularly devastating for low-income and minority children—and their parents. One nationwide survey co-sponsored by the Associated Press found that just one in four Black and Hispanic students has access to in-person instruction. As K-12 education, or some crude approximation of it, becomes a stay-at-home affair, parents are being pulled out of the workforce to serve as teachers. No surprise, the school-closing pandemic is mostly a tax on working mothers. Married women lost almost 1 million jobs last month, while overall employment surged.

America can’t go back to normal without school. But Americans don’t have to choose between health and education, or between health and parental sanity. Japan’s example proves that.

After containing the spread of the virus—more or less the same way South Korea did—it worked to virus-proof the classroom, as much as possible. In Japan, where most schools are back in session, schools have largely avoided outbreaks by enforcing universal mask wearing, encouraging kids to socially distance, and installing cheap plastic shields to interrupt the flow of aerosolized particles between students. Using advanced computer models, Japanese researchers have demonstrated that cracking open a window and a door on opposite sides of a temperature-controlled room can properly ventilate a class with dozens of students. Masks, distancing, and ventilation: Yes, it might really be that simple.

Beating a pandemic is sometimes compared to a war, which brings to mind total sacrifice to defeat an evil enemy. But the problem with the war analogy is that it conjures a kind of all-or-nothing approach to virus mitigation. The West could dramatically improve its lot if it adopted a small number of measures to defeat the virus that are empirical, imperfect, and just enough.